Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Defining Pneumothorax

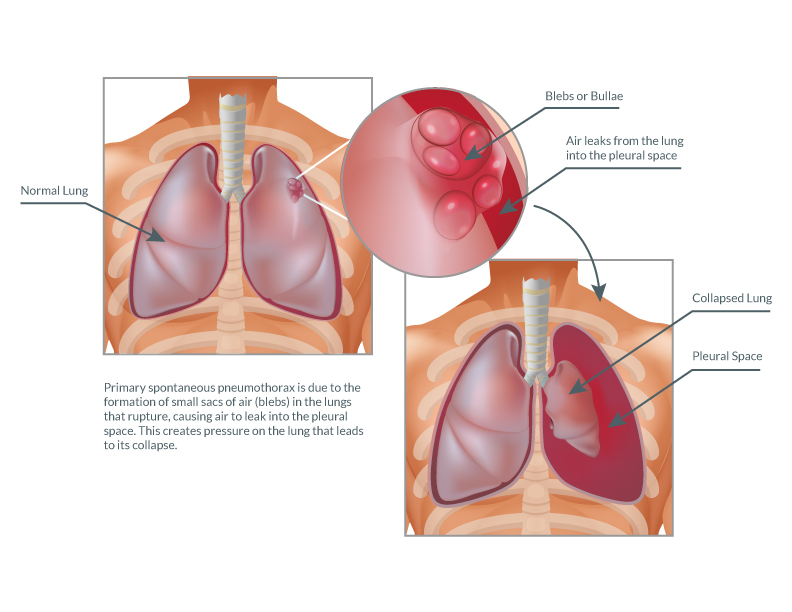

Pneumothorax is the abnormal presence of air in the space between the lungs and the chest cavity (known as the pleural space), which can lead to a partial or complete collapse of the respective lung.

Pneumothorax can be classified as:

- Traumatic (result of an accident or other medical treatment), or

- Spontaneous

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Terms

Spontaneous pneumothorax can be termed as:

- Primary (PSP) in the absence of any obvious precipitating factor, or

- Secondary (SSP) when associated with underlying pulmonary diseases or conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, malignancy, etc.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is generally made through a conventional chest X-ray. However, a CT scan is indicated to provide more detailed information.

Causes and Symptoms

Most cases of primary spontaneous pneumothorax are due to the formation of small sacs of air (blebs) in the lungs that rupture, causing air to leak into the pleural space. This creates pressure on the lung that leads to its collapse.

Blebs themselves do not cause any symptoms and may be present for a long time before they rupture (if they rupture). Typically, the result of a rupture is the acute onset of chest pain and shortness of breath. However, up to 10 percent of patients may be asymptomatic while others have such mild symptoms that they may not even seek out medical care.

Risk Factors

Although the underlying cause of PSP is still poorly understood, the following correlations and risk factors have been established for primary spontaneous pneumothorax:

- Smoking

- Gender (men are 3.3 times more likely than woman to experience this)

- Age (18 to 40 years old)

- Stature (tall, thin)

- Familial pneumothorax

- Genetic disorders

To elaborate, PSP is strongly related to smoking in both sexes; with the risk increasing by more than 20-fold in men and by nearly 10-fold in women compared with the risks in nonsmokers. Smoking causes inflammation in the small airways leading to tissue damage referred to as emphysematous-like changes (ELCs).

In general, PSP is more common in men than women. The annual incidence is 7.4 to 18 per 100,000 men and 1.2 to 6 per 100,000 women. A first peak of incidence occurs at 20 to 25 years in men, and some studies have found that the first peak in women is delayed at 30 to 34 years of age.

Typically, patients tend to have a tall and thin body habitus. However, it is unclear whether height affects development of subpleural blebs or whether more negative apical pleural pressure causes pre-existing blebs to rupture.

Familial clustering of this condition has been reported in more than 10 percent of patients. Genetic disorders that have been linked to PSP include Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria and Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (BHD).

Contrary to popular belief, physical effort has not been substantiated as a precipitating factor; PSP typically occurs at rest. Other precipitating factors described (although controversial) include:

- Atmospheric pressure changes

- Exposure to loud music

- Pregnancy (which is an unrecognized risk factor)

Managing Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Treatment options for spontaneous pneumothorax include:

- Close observation

- Chest tube insertion

- Surgical intervention utilizing a video-assisted approach

The choice of management option depends on many factors including whether this is a first time pneumothorax or a recurrent one. With first-time pneumothoraces, conservative management is generally recommended.

Complete resolution of an uncomplicated pneumothorax can take up to 10 days. The five-year recurrence rate for PSP ranges from 28 to 32 percent, most of them taking place within 1 to 2 years after the first episode.

Some pneumothoraces are small and confined to the top of the lung; these can often be observed with close follow up. The majority of these patients have complete resolution of the problem and approximately 80 percent will have no further problems with collapse of the lung.

In the case of a larger pneumothorax, treatment usually entails placing a chest tube in the lung for re-expansion and allowing it to heal. This requires the tube to remain in place for several days. Often this can be managed as an outpatient.

Surgery is indicated in two situations:

- If the lung remains unexpanded after the chest tube has been in place for an adequate period of time, or

- If a recurrent pneumothorax occurs

With the latter, the incidence of a chronic and recurring problem goes up greatly; therefore more definitive surgical management would be recommended.

The surgical procedure involves using a minimally invasive technique in which the apical blebs are removed along with a portion of the lining of the chest (pleura). This technique allows the top of the lung to adhere to the chest wall whereby preventing a future collapse. Surgery typically requires just one overnight stay at the hospital and a short recovery at home.

In our experience, this treatment has been extremely effective, and our patients have less than a one percent recurrence after surgery.